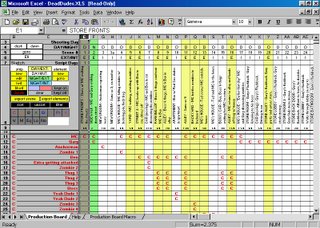

PRE PRODUCTION (continued)STEP 1. BREAK DOWN YOUR SCRIPT (cont.)STEP 1b: The Production Board (cont.)III. Shooting ScheduleFilmmaker's Software and the other Scheduling/Budgeting software packages out there do more than just create strips. They create shooting schedules, call sheets, budgets, daily reports, contacts sheets and more. That stuff comes later. For now we have to nail down a shooting schedule.

When you've entered in your last strip, what you have is a grid-based representation of your movie. Right in front of you is a description of every scene and everything that's necessary for every scene. The problem is, it's all in the order that the script dictates. It starts with Scene One and ends with Scene Whatever (let's say 80). What we now need to do is create a shooting schedule that makes sense for the logistics of our particular wants/needs.

Now, a shooting schedule requires a lot of common sense. Chances are, you won't be able to shoot your movie in sequence, so you're going to need to figure out what scenes make sense to group together to shoot on certain days.

Plan on having each day be 8-10 hours long. And here's where the page count starts to help us out -- try not to schedule more than 10 pages a day.

There are exceptions, of course. If you have a 15 page scene that takes place in a controlled environment, is all dialogue, and you have really good actors who will know their lines... then sure, you'll be able to get away with that. Also to consider -- if you have a 15 page scene with two people doing nothing but talking, you may want to take another look at the script. Outside of MY DINNER WITH ANDRE (great director, brilliant actors), I haven't seen that pulled off too many times.

So, how many pages can you shoot in 8-10 hours? It depends. A good target is 6-9 pages. You figure most scenes are about 2 pages long. Some longer, some shorter, but they average out. That means three scenes per day, which requires three lighting set ups, three blocking rehearsals (where the actors rehearse the scene with the director and director of photography to figure out 'who says what where', and 'who walks where when', and how am I going to light it? Blocking and lighting will probably take at least an hour; break down and moving will take half an hour; that four and half hours and you haven't even shot a single frame of tape (note I didn't say: "you haven't shot a single foot of film." Nobody but nobody is making a movie with film in this budget range).

My point here is that half of your day is devoted to

not shooting. Sometimes, it's a lot more. There were days on MAGDALENA'S BRAIN where we shot 3 pages in 12 hours.

So anyway. Let's say 8 pages a day. How's long the script? 77 pages? So, we're looking at 9-10 days of shooting.

This is going to be difficult.

There are two basic approaches you can make in developing a shooting schedule.

-Shoot all at once, in consecutive days.-Shoot when you can, weekends/nights, whenever possible.Both have their strengths and weaknesses. I certainly have a preference, but sometimes necessity dictates which way you go.

We shot MAGDALENA'S BRAIN in 14 days, with two days off within a 16 day period. The result was exhausting, but after 14 days, we had the movie in the can. We also had the luxury of a modest -- but still well over $1,000 -- budget. Which meant we were able to pay people

something who were taking time off of their regular jobs, or turning down other work that may have come their way.

With $1,000 in the budget, you can be sure you'll have to shoot your movie the second way -- nights and weekends. I always prefer to shoot consecutive days. I've been involved with both approaches, and the piecemeal way has a lot more cons than pros.

-Creating a schedule is made much more difficult.-Continuity is a nightmare.-Consistent performances are difficult.-Excitement wanes, followed by attendance.There are other cons, to be sure. But the above are enough of a bear to work around. The pros?

-Exhaustion is unlikely.-Sanity is maintained.-You don't have to pay people.Insanity and exhaustion are key elements to pretty much any shoot, but only reach dangerous levels when you've got three, four, six, 12+ days in a row. Onesies and twosies on a Saturday or Sunday? You'll still have your mind intact, though I think you're actually missing out on something of the filmmaking experience to shoot like this.

It's that last pro that makes this pretty much the required route. Nobody will take 10 days off of work to help you make your movie.

Let's break down the cons, and find some ways to alleviate the negative. Just because we have to deal with them doesn't mean we have to let them kick our ass.

-Creating a schedule is made much more difficult. Damn, is it ever.

What you're forced to do here determine who are going to be the most important people in your production, and then customize the schedule around them. For me, the list looks something this:

#1. You

#2. The director of photography

#3. The sound mixer#4. The actors

I think it's extraordinarily important to have the same guy holding the camera every time you shoot. Or at least, as often as humanly possible. The responsibility of lighting, composing and shooting your movie should not fall on your little brother. And it should certainly not fall on you, either. You're going to have your hands full with a million other things, not the least of which are performances. It's tough to direct actors while looking through a viewfinder.

So, if it's not you or your little brother... who is it going to be? We'll get to that in a bit. Just keep in mind that it's a very good idea to consider your DP your right-hand man throughout production, and your schedule should reflect the importance of that relationship.

And a sound mixer? Can you afford a sound mixer? Actually, no... you probably can't, but there are some good cheap cheats that I can fill you in on later. Just make sure you always have someone on site in charge of audio.

So, if

you're not available, don't shoot.

If your DPs not available, you probably shouldn't shoot.

And, if no one knows anything about the audio, you probably shouldn't shoot.

But you're going to know everybody's personal schedule weeks before you shoot. And knowing their schedules is going to help you you make yours.

Oh wait... what about the actors? Well, you can't shoot without them, I guess. But here's the thing (and we'll talk more about this later), they'll always make themselves available. I love actors, really I do. And we couldn't do what we do without them, but here's the thing -- they're desperate to do anything. If you've got a pretty good script, you will have no shortage of bad and mediocre actors lining up at 4:00am on a Sunday morning to get covered in pig's blood. Good actors? They're desperate, too, just tougher to find.

Great actors you probably won't have to worry about.

-Continuity is a nightmare.Continuity is hard enough... when you start putting 6-7 days between shoots, it can become downright impossible. On proper shoots, you'd have a script supervisor, a person who is never without a three ringed binder containing their own personal copy of the script. This copy has crazy notes in the margins, between dialogue, sometimes on the back. The have scribbly code like

47A.1 Left hand-cup (3/4). No drink. Hair - front right ear, pulls back on "...gel suspended in cystalline lattice".Roughly translated, we're shooting scene 47A. An actor, who has a 3/4-filled cup in her left hand but doesn't drink from it, pulls the hair in front of her right ear back, as she delivers the line "...gel suspended in cystalline lattice". This is what a script supervisor/continuity person does. All day.

Below find a sample page from MAGDALENA'S BRAIN, created by our own script supervisor, Maria Escribano:

They also prepare tape logs, which log every take of every scene -- everything recorded gets noted here. On these, they also write things like:"47A . 1 - No. 47A.2 - Good, good. One more for safety. 47A.3 Good safety. Moving on."

Translated, that means that Scene 47A was being shot. Take one (.1) was no good... the director said "No"; for take 2, the director said, "good, good". But he decided he wanted another take "for safety". Take three was a good safety and it was decided to move on to the next scene.

Without a script supervisor to even tell you what color pants Jill was wearing last weekend, you'd better have a real good memory.

******************MONEY / TIME SAVING HINT*******************

At the end of each scene, and the each shooting day, take digital photos of each of your actors. Keep them in a log to SEE what each actor looks like in different parts of the movie.

*******************************

-Consistent performances are difficult.

You're probably dealing with amateur actors, so an irregular shooting schedule is going to make it that much more difficult to get consistent performances out of them. When an actor is living with a character day in, day out, they start to inhabit a strange place. It's kinda of scary sometimes (I don't get actors). When actors work 40 hours selling envelopes in between shoots, the performance is sure to suffer.

******************GOOD PERFORMANCE HINT*******************

Rough cut scenes together in between shoot and share them with the cast. It'll help actors "get in character".

*******************************

-Excitement wanes, followed by attendance.

Conceptually, filmmaking is the coolest thing ever. The idea of making movies is glamorous, romantic and profound. The thought of the lights, of the camera, of the action...it's intoxicating.

In reality, it's unbelievably tedious, boring and staggeringly repetitive.

When you're roping people into your filmmaking experience, you're going to get a lot of newbies. And these newbies aren't all going to last. By the third shoot day, they're going to realize that the first two boring days weren't just the exception, but rather the rule.

*

The above are some cons. But remember the pro:

-You don't have to pay people.

(continued)

© 2006 by Marty Langford